A “New Cold War”?

“The silence of slippers is more dangerous than the sound of boots.”

By Louis Perez y Cid

The war in Ukraine has shattered a persistent illusion: that of a Europe definitively removed from the history of power relations.

Beyond the fighting, a long-term confrontation has taken hold between the West and Russia. A confrontation destined to last, with no quick solution or new security order on the horizon.

However, a major war between Russia and NATO remains unlikely. Nuclear deterrence continues to play its role, solidifying red lines and preventing escalation into all-out conflict. But the absence of open war does not mean peace.

Because another war is already here. More discreet, more diffuse. It unfolds in the gray areas: limited military pressure, cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, sabotage, attempts to destabilize European societies. A “new Cold War” has taken hold, and we are fully involved in it.

Consequently, one question keeps recurring: does France have enough soldiers? Contrary to popular belief, the answer is generally yes.

The French Army has sufficient personnel for this type of confrontation, provided it fully utilizes all its resources. Comparing our situation to the Ukrainian war of attrition is misleading. France is operating within a collective framework, that of NATO, for the time being, and its mission is not to sustain a protracted war, but to deter, contain, and react swiftly. The active-duty army forms its core. Alongside it, the reserve is becoming essential, particularly for the protection of the territory and the reinforcement of forces in the event of a crisis. The planned doubling of its personnel by 2030 is a major asset, provided that real resources are allocated to it. Read more...

The war in Ukraine has shattered a persistent illusion: that of a Europe definitively removed from the history of power relations.

Beyond the fighting, a long-term confrontation has taken hold between the West and Russia. A confrontation destined to last, with no quick solution or new security order on the horizon.

However, a major war between Russia and NATO remains unlikely. Nuclear deterrence continues to play its role, solidifying red lines and preventing escalation into all-out conflict. But the absence of open war does not mean peace.

Because another war is already here. More discreet, more diffuse. It unfolds in the gray areas: limited military pressure, cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, sabotage, attempts to destabilize European societies. A “new Cold War” has taken hold, and we are fully involved in it.

Consequently, one question keeps recurring: does France have enough soldiers? Contrary to popular belief, the answer is generally yes.

The French Army has sufficient personnel for this type of confrontation, provided it fully utilizes all its resources. Comparing our situation to the Ukrainian war of attrition is misleading. France is operating within a collective framework, that of NATO, for the time being, and its mission is not to sustain a protracted war, but to deter, contain, and react swiftly. The active-duty army forms its core. Alongside it, the reserve is becoming essential, particularly for the protection of the territory and the reinforcement of forces in the event of a crisis. The planned doubling of its personnel by 2030 is a major asset, provided that real resources are allocated to it. Read more...

The Venezuela Question

By Louis Perez y Cid

My friend Paco, a veteran of the 13th Legion, along with other former legionnaires from Maracaibo, Venezuela, are "outraged" by the US action in Caracas and are asking me what we think about it here in France.

My friend Paco, a veteran of the 13th Legion, along with other former legionnaires from Maracaibo, Venezuela, are "outraged" by the US action in Caracas and are asking me what we think about it here in France.

When the dollar becomes the central issue

Paco,

I received your message. I understand your anger, and that of the other Maracaibo veterans. From here, what's happening in Caracas isn't really surprising anymore, but it's still shocking. So I'm going to tell you frankly what many people think, without mincing words.

We're still being told that all of this is a matter of democracy, drug trafficking, and an authoritarian regime. That's the official line, the one that goes over well on television. But that's not where the real issue lies. Venezuela isn't being attacked for what it is, but for what it possesses and for what it dares to question.

For nearly fifty years, oil has spoken in dollars. It's an unwritten but sacred rule. Thanks to it, the United States built a financial and military power that no one could truly challenge. As long as oil was sold in dollars, the order held. And those who tried to deviate from it were brought back into line, violently.

Venezuela, with its immense reserves, crossed a red line. By diversifying its currencies, by forging closer ties with the BRICS, by engaging in discussions with China, Russia, and Iran, Caracas did what few states dare to do: touch the heart of the system. History has already shown us this, in Iraq and Libya. This kind of initiative never goes unpunished. Read more...

I received your message. I understand your anger, and that of the other Maracaibo veterans. From here, what's happening in Caracas isn't really surprising anymore, but it's still shocking. So I'm going to tell you frankly what many people think, without mincing words.

We're still being told that all of this is a matter of democracy, drug trafficking, and an authoritarian regime. That's the official line, the one that goes over well on television. But that's not where the real issue lies. Venezuela isn't being attacked for what it is, but for what it possesses and for what it dares to question.

For nearly fifty years, oil has spoken in dollars. It's an unwritten but sacred rule. Thanks to it, the United States built a financial and military power that no one could truly challenge. As long as oil was sold in dollars, the order held. And those who tried to deviate from it were brought back into line, violently.

Venezuela, with its immense reserves, crossed a red line. By diversifying its currencies, by forging closer ties with the BRICS, by engaging in discussions with China, Russia, and Iran, Caracas did what few states dare to do: touch the heart of the system. History has already shown us this, in Iraq and Libya. This kind of initiative never goes unpunished. Read more...

The Greenland Question

By Louis Perez y Cid

Through this text, I salute Peter, his wife Kirsten, Lars, and our other former legionnaires living in Denmark.

Through this text, I salute Peter, his wife Kirsten, Lars, and our other former legionnaires living in Denmark.

A world we talk about without ever listening to those who inhabit it

In June 1951, after many months spent among the Inuit of northwest Greenland, Jean Malaurie* witnessed an unreal vision emerge from the tundra: a city of metal, hangars, and smoke. Where silence and hunting still reigned, the secret American base of Thule had just been born. For the explorer, this emergence marked an irreversible shift, that of the Inuit world.

In one summer, the United States deployed 12,000 men and an entire fleet to build, on frozen ground, one of its largest military bases abroad.

The threat of a Soviet attack via the polar route served as justification. For the Inuit, it was a silent annexation, the brutal intrusion of a world of machines, speed, and nuclear weapons into a world governed by hunting and the rhythms of life.

In one summer, the United States deployed 12,000 men and an entire fleet to build, on frozen ground, one of its largest military bases abroad.

The threat of a Soviet attack via the polar route served as justification. For the Inuit, it was a silent annexation, the brutal intrusion of a world of machines, speed, and nuclear weapons into a world governed by hunting and the rhythms of life.

The American Presence

The American presence in Greenland, however, did not begin with the Cold War. As early as 1941, after the Nazi occupation of Denmark, the United States established several bases there to secure the North Atlantic and air routes to Europe. The defense agreement signed in 1951 between Washington and Copenhagen formalized this presence and allowed for the construction of Thule. Read more...

Did you say European Community*?

By Louis Perez y Cid

The Story of a Power That Gave Up

I am talking about our Europe, not as it is portrayed, but as it has objectively become within the international system.

Here I highlight the power dynamics, which is precisely the role of history.

Here I highlight the power dynamics, which is precisely the role of history.

The European Paradox

Europe is a historical paradox.

It is the continent that invented the modern state, sovereignty, taxation, industrial warfare, capitalism, international law, and political universalism. It dominated the world for several centuries before collapsing under the weight of its own rivalries.

Today, Europe is neither poor nor weak in a material sense. It is rich, educated, technologically advanced, and demographically significant. Yet, it is no longer a sovereign political power. It is more acted upon than acted upon. It reacts more than it decides.

This decline is not accidental. It is the product of a specific history.

It is the continent that invented the modern state, sovereignty, taxation, industrial warfare, capitalism, international law, and political universalism. It dominated the world for several centuries before collapsing under the weight of its own rivalries.

Today, Europe is neither poor nor weak in a material sense. It is rich, educated, technologically advanced, and demographically significant. Yet, it is no longer a sovereign political power. It is more acted upon than acted upon. It reacts more than it decides.

This decline is not accidental. It is the product of a specific history.

Europe before Europe: Power, Conflict, and Self-Destruction

The Old Legionnaire's Christmas

A story by Christian Morisot

The scene depicts the spot on the Vède River in front of the bridge where a kind of reservoir forms a natural pool... A group of young people arrive at this enchanting view. Opposite the Vède River, on the Vède estate, an old legionnaire calls out to them:

• Hey! What are you doing here, children? It's a dangerous place; you could fall in!

• But, sir, we're not doing anything wrong. Our parents always told us that when they were young, they used to come with their families to see the kind old legionnaires and even swim here in the Vède.

• Yes, but they came with their families and were supervised!

• We're not here to swim, sir. We've just come to see where "Bambi" was killed. Read more...

The scene depicts the spot on the Vède River in front of the bridge where a kind of reservoir forms a natural pool... A group of young people arrive at this enchanting view. Opposite the Vède River, on the Vède estate, an old legionnaire calls out to them:

• Hey! What are you doing here, children? It's a dangerous place; you could fall in!

• But, sir, we're not doing anything wrong. Our parents always told us that when they were young, they used to come with their families to see the kind old legionnaires and even swim here in the Vède.

• Yes, but they came with their families and were supervised!

• We're not here to swim, sir. We've just come to see where "Bambi" was killed. Read more...

_(1).jpg?t=17dd34a1_7cef_4edb_a5bf_05202457291f)

A Christmas Tale from History

Sometimes, history writes its own tales. This text by Antoine speaks of courage, forgetting, loyalty, and reunion. Two soldiers, two parallel lives, a belated encounter that illuminates their shared past. This foreword invites the reader into a story where reality surpasses fiction and where brotherhood survives everything: wars, years, and silence.

Louis Perez y Cid

Louis Perez y Cid

Tale or Miracle?

By Antoine Marquet

Miracles still exist, even in the Colonial Army.

A few days ago, I was browsing Facebook when the weathered face of a veteran, covered in medals, appeared on my screen. The caption read: "The last survivor of Dien Bien Phu." I smiled and replied: No. He's not the last one.

I know another. A 91-year-old man, straight as an oak, his eyes twinkling: Raymond Lindemann, my friend of forty years.

Raymond, parachuted into Dien Bien Phu with his battalion, held out until the camp fell, before the long night of captivity with the Viet Minh. Read more...

Miracles still exist, even in the Colonial Army.

A few days ago, I was browsing Facebook when the weathered face of a veteran, covered in medals, appeared on my screen. The caption read: "The last survivor of Dien Bien Phu." I smiled and replied: No. He's not the last one.

I know another. A 91-year-old man, straight as an oak, his eyes twinkling: Raymond Lindemann, my friend of forty years.

Raymond, parachuted into Dien Bien Phu with his battalion, held out until the camp fell, before the long night of captivity with the Viet Minh. Read more...

These Women Who Hold the Line

Behind every soldier, there is a woman. A support base. A silent force.

Without her, the soldier's commitment would be much more difficult. She holds the line while he is on a mission.

Yet, her role remains too often invisible, reduced to support tasks, as if the essentials were self-evident.

This is the subject of Christian's text, which also mentions the Veterans' Associations, where many women keep the structures running: treasury, secretariat, organization, continuity. Their commitment is real, constant, and indispensable.

They are not in the background; they are often at the heart of it.

Without them, many Veterans' Associations would not function.

Louis Perez y Cid

"Against All Odds..."

By Christian Morisot

Discussion:

Absences pile up, and comments often fly, sometimes clumsily: "At least your husbands have job security! He's already back, how quickly did it go?" You knew it when you got married, etc…

Being a military wife means taking on her husband's job, come what may. It means accepting long deployments, frequent moves, weekend shifts and on-call duty, and leave rather than vacation time.

A true pillar of the family, the military wife learns selflessness and dedication. Yet, for her, nothing is easy; there are moments of doubt and breakdown, contrary to popular belief. Unless she lives in a geographically isolated location or can work from home, it's rare that she can't find work, often due to a transfer every two or three years…Read more...

Opening of the Christmas Season

By Louis Perez y Cid

In the French Foreign Legion, time doesn't flow quite like anywhere else. It is punctuated by powerful landmarks, laden with memory and meaning. Among them, two dates stand out and resonate with each other.

Camerone, on April 30th, celebrates military virtues taken to the ultimate sacrifice. Courage, honor, fidelity to one's word, even when all seems lost. It is the celebration of combat, of total commitment, of the man who stands tall until the very end.

And then there is Christmas.

Another victory, more silent. A celebration that glorifies not the weapon, but the man. Family, solidarity, brotherhood. Everything that allows the legionnaire to remain human, despite the harshness of the profession and the isolation. Read more...

In the French Foreign Legion, time doesn't flow quite like anywhere else. It is punctuated by powerful landmarks, laden with memory and meaning. Among them, two dates stand out and resonate with each other.

Camerone, on April 30th, celebrates military virtues taken to the ultimate sacrifice. Courage, honor, fidelity to one's word, even when all seems lost. It is the celebration of combat, of total commitment, of the man who stands tall until the very end.

And then there is Christmas.

Another victory, more silent. A celebration that glorifies not the weapon, but the man. Family, solidarity, brotherhood. Everything that allows the legionnaire to remain human, despite the harshness of the profession and the isolation. Read more...

France as Heritage

These few pages are a reflection born on the parade ground in Aubagne, at the very moment when young legionnaires were receiving their naturalization certificates. Watching them become French, a question arose for Christian: what does France truly mean to those who join it by choice? This text is an attempt at an answer, nourished by experience, memory, and a deep attachment to the republican motto that guides our country.

But this emotion takes on a particular meaning when experienced within the Foreign Legion. For the Legion is not merely a military formation; it is a place of rebirth, of transcendence, of tangible brotherhood, where men from all over the world learn a language, a spirit, a shared discipline. For some, it even becomes the path to a new homeland. It is to these men, to these new compatriots who have already served France even before receiving their official documents, that these lines are addressed. They want to celebrate their commitment, to recall the strength of the bond that unites the Legion to the Nation, and to convey what it truly means to inherit France: a history, values, an ideal, but also a duty of fraternity, loyalty, and solidarity, which have always been at the heart of the Legion.

Louis Perez y Cid

By Christian Morisot.

Fleetingly, the evening light envelops the parade ground of the Viénot barracks in Aubagne in a dark mass. A very special event was taking place: a group of young legionnaires were being presented by local elected officials with a certificate confirming their French naturalization. Pleasantly charmed by the unexpected nature of these young men's commitment, a question came to mind: "What could France possibly represent for them? What image and opinion might they have of the history of their new country?" I impulsively felt frustrated at not being able to speak to them, not to lecture them, but simply to tell them what France represents for many of the former legionnaires who, long before their voluntary act, had also chosen to become French. Read more...

Marshal Pétain 3 and end

By Christian Morisot

In response to my friends Louis and Michel.

First and foremost, a question arises: "What would become of our feelings if the Marshal's trial did not take place…?" This question, posed in this way, leads to another: "Why should this be of serious interest to a foreigner serving France?"

Nevertheless, the subject is fascinating for some of us and extends far beyond the intimate thoughts that each of us keeps deep within our memories. Michel's reaction is bold but uncompromising, to the point of concluding that: "History, nothing but history. The rest is just talk." In fact, Michel's response raises a completely different point: that one day you are an adored hero and the next the worst of villains! Hope in 1940 had not changed sides, however, the struggle itself had changed its very essence, embodied by a resistance whose numbers were particularly impressive at the time of the liberation of the free world… Read more

In response to my friends Louis and Michel.

First and foremost, a question arises: "What would become of our feelings if the Marshal's trial did not take place…?" This question, posed in this way, leads to another: "Why should this be of serious interest to a foreigner serving France?"

Nevertheless, the subject is fascinating for some of us and extends far beyond the intimate thoughts that each of us keeps deep within our memories. Michel's reaction is bold but uncompromising, to the point of concluding that: "History, nothing but history. The rest is just talk." In fact, Michel's response raises a completely different point: that one day you are an adored hero and the next the worst of villains! Hope in 1940 had not changed sides, however, the struggle itself had changed its very essence, embodied by a resistance whose numbers were particularly impressive at the time of the liberation of the free world… Read more

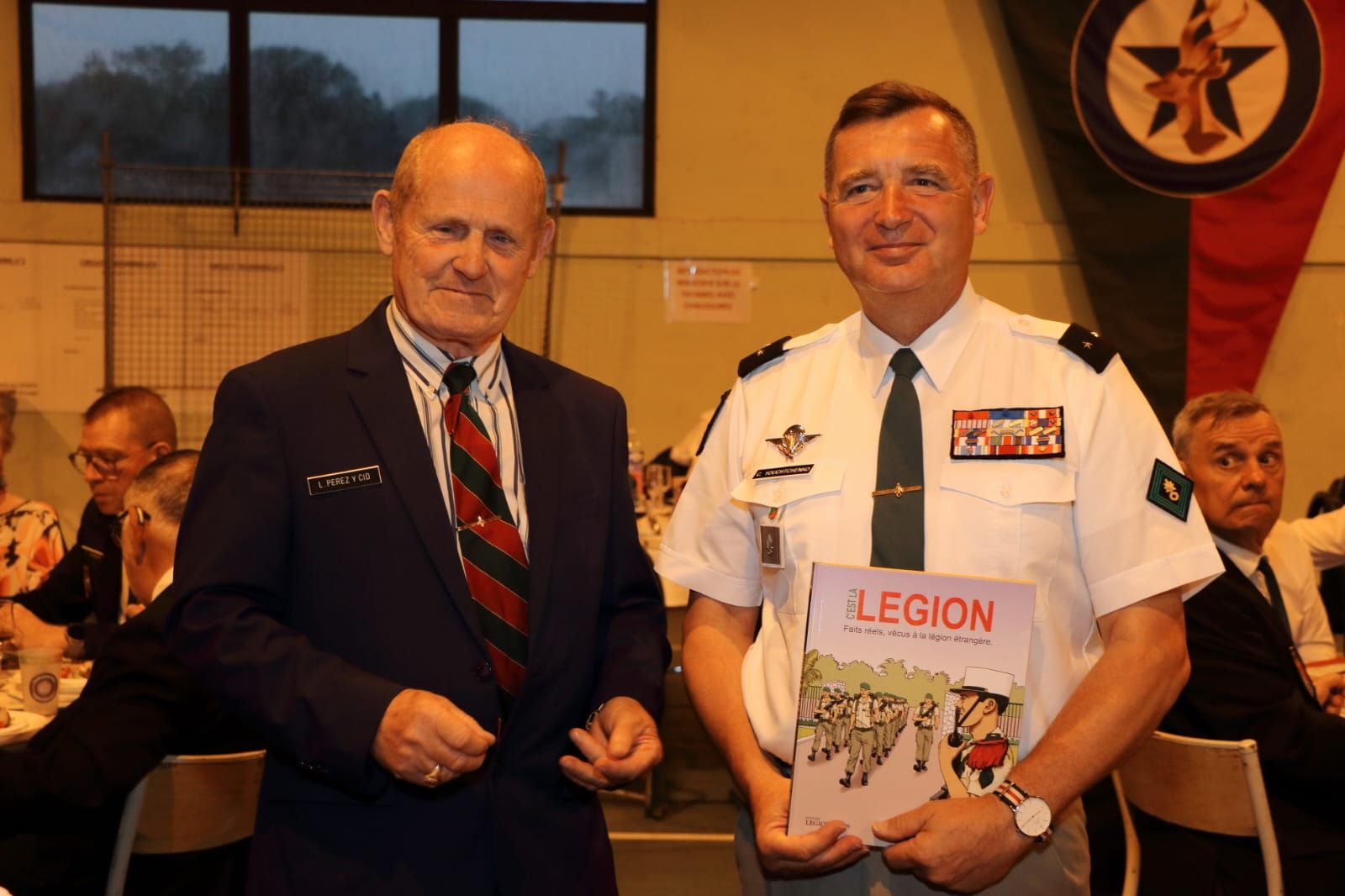

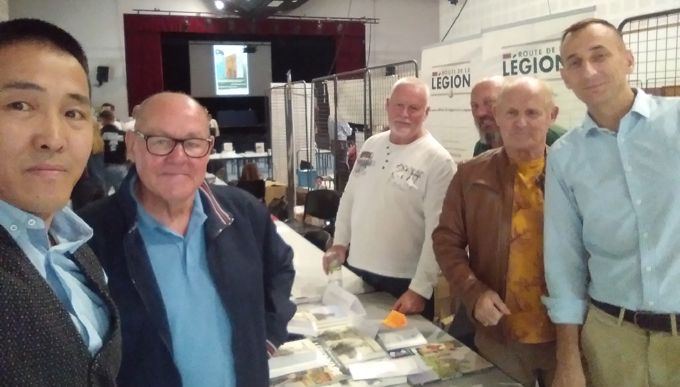

Our Latest Events

While the website opened on October 1st, Légion'arts has been active for much longer. Here's a summary of the latest events.

FSALE Congress. June 13-14-15

The comic book "C'est la légion" is published by Légion'arts specifically for this event. It should be noted that it was created voluntarily by members of our association, including the scripts, drawings, and coloring.

The printing of 3,000 albums is financed by FSALE. Profits from sales are dedicated to FSALE.

By purchasing an album, you contribute to the federation's charitable work—another way to make a donation.

The printing of 3,000 albums is financed by FSALE. Profits from sales are dedicated to FSALE.

By purchasing an album, you contribute to the federation's charitable work—another way to make a donation.

Book signing weekend in Orange. September 13-14

Paella and book signings. September 20.

A book signing session benefiting the AALE of the Pays dAix and the Ste Baume, was held under the plane trees of the Capitaine Danjou estate.

Cocktail Party. COMLE. September 26.

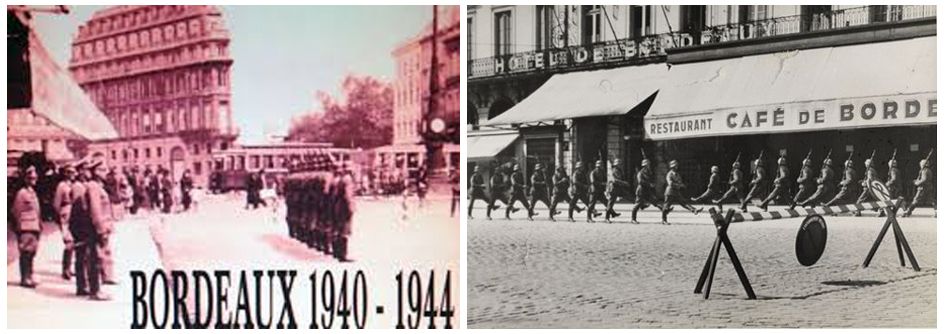

Marshal Pétain

By Michel Gravereau

Hello Louis,

I would like to respond quickly to your article published this morning about Marshal Pétain.

I was born just after the war, and throughout my childhood, I heard people in my family, at various houses, talking about Pétain. The Marshal for some, the collaborator for others. Depending on whether you were powerful or destitute…

The subject was a hot topic. What I have always remembered is that I lived among ordinary French people who were suffering under the German occupation. My mother often told me: "We saw the Germans marching across the stone bridge in Bordeaux. Is that a troop encountering resistance?"

We could, unfortunately, recall the tragic fate of glorious Legion regiments, the 11th and 12th REI, to name just two. Crushed despite their bravery.

Where were the politicians to offer resistance? Read more...

Hello Louis,

I would like to respond quickly to your article published this morning about Marshal Pétain.

I was born just after the war, and throughout my childhood, I heard people in my family, at various houses, talking about Pétain. The Marshal for some, the collaborator for others. Depending on whether you were powerful or destitute…

The subject was a hot topic. What I have always remembered is that I lived among ordinary French people who were suffering under the German occupation. My mother often told me: "We saw the Germans marching across the stone bridge in Bordeaux. Is that a troop encountering resistance?"

We could, unfortunately, recall the tragic fate of glorious Legion regiments, the 11th and 12th REI, to name just two. Crushed despite their bravery.

Where were the politicians to offer resistance? Read more...

Marshal Pétain

By Louis Perez y Cid

The controversy surrounding the mass for Marshal Pétain on November 14, 2025, has reignited a typically French polarization: the mayor of Verdun, from the left, opposes it; a right-wing association takes legal action. What should be a calm debate about history immediately becomes an ideological clash. In France, questions of memory too often serve as political battlegrounds.

Like many former legionnaires of foreign origin, I observe this country with respect but also with perplexity. A naturalized Frenchman, like myself, does not inherit the political landmarks passed down within families, landmarks that have shaped the left-right divide for over a century. France is a centralized state, where political life occupies a disproportionate place; even those who are disinterested in it end up taking sides. Read more...

November 11

By Christian Morisot

As president of a veterans' association, I became interested in the national holiday of November 11 to recall the "mourning within the celebration" that mobilized veterans of the Great War to hold a commemoration three years after the anniversary of the signing of the armistice, thus marking what they called "the end of the most appalling slaughter that has ever devastated the modern world."

Thus, it was the veterans themselves who established November 11 as a national holiday. In 1921, Parliament, anxious to combat long weekends, postponed the Armistice Day celebration to Sunday the 13th. This provoked a general outcry from all veterans' associations, who ultimately prevailed.

The appeal to the people to celebrate this national holiday was expressed as follows:

“For fifty-two months, entire nations clashed on vast battlefields. Forty million men fought. The men of war want their victory to consecrate the crushing of war.” Read more...

As president of a veterans' association, I became interested in the national holiday of November 11 to recall the "mourning within the celebration" that mobilized veterans of the Great War to hold a commemoration three years after the anniversary of the signing of the armistice, thus marking what they called "the end of the most appalling slaughter that has ever devastated the modern world."

Thus, it was the veterans themselves who established November 11 as a national holiday. In 1921, Parliament, anxious to combat long weekends, postponed the Armistice Day celebration to Sunday the 13th. This provoked a general outcry from all veterans' associations, who ultimately prevailed.

The appeal to the people to celebrate this national holiday was expressed as follows:

“For fifty-two months, entire nations clashed on vast battlefields. Forty million men fought. The men of war want their victory to consecrate the crushing of war.” Read more...

What the French Soldiers Wanted to Pass on to the Nation

This article is addressed to former legionnaires, who come from many countries but are united by their attachment to France.

Many of them did not grow up with the family history of the Great War, which is why it is important to understand its profound meaning, as the French veterans, the poilus, intended it.

A Day of Silence, Not Triumph

On November 11, 1918, at 11:00 a.m., the guns finally fell silent.

The Armistice brought an end to more than four years of a terrible war. The trenches, the mud, the cold, the gas, and the shells had forever marked an entire generation.

Nearly 1.4 million French soldiers had given their lives to defend the homeland.

Yet, when peace returned, the veterans did not want to celebrate a resounding victory.

On the contrary, they asked that this date be dedicated to remembrance:

a time for reflection, not for parades; A national silence, not a triumphal march.

“What we want is for our fallen comrades to be remembered, not for the war to be celebrated.”

Testimony of a French soldier, 1919

The spirit of the French soldiers: to honor, not glorify

The French soldiers knew that peace would only last if the price it had cost was remembered.

They wished that every November 11th, France would bow before the courage of those who had fallen and thank those who had held firm in the hell of the trenches.

Thus was born the idea of a day of national unity, where the entire nation, from elected officials to children, pays tribute to its soldiers.

Not to exalt strength, but to honor loyalty and sacrifice.

Many of them did not grow up with the family history of the Great War, which is why it is important to understand its profound meaning, as the French veterans, the poilus, intended it.

A Day of Silence, Not Triumph

On November 11, 1918, at 11:00 a.m., the guns finally fell silent.

The Armistice brought an end to more than four years of a terrible war. The trenches, the mud, the cold, the gas, and the shells had forever marked an entire generation.

Nearly 1.4 million French soldiers had given their lives to defend the homeland.

Yet, when peace returned, the veterans did not want to celebrate a resounding victory.

On the contrary, they asked that this date be dedicated to remembrance:

a time for reflection, not for parades; A national silence, not a triumphal march.

“What we want is for our fallen comrades to be remembered, not for the war to be celebrated.”

Testimony of a French soldier, 1919

The spirit of the French soldiers: to honor, not glorify

The French soldiers knew that peace would only last if the price it had cost was remembered.

They wished that every November 11th, France would bow before the courage of those who had fallen and thank those who had held firm in the hell of the trenches.

Thus was born the idea of a day of national unity, where the entire nation, from elected officials to children, pays tribute to its soldiers.

Not to exalt strength, but to honor loyalty and sacrifice.

The First Commemoration (1920)

The first November 11th ceremony took place in 1920, two years after the Armistice.

The French Parliament decided to make it an official day of remembrance and to bury an unknown soldier beneath the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

This soldier, chosen from among the unidentified dead of the front, represents all the anonymous heroes.

Three years later, in 1923, the journalist Gabriel Boissy proposed lighting a flame of remembrance above the tomb.

Since that day, the flame has never been extinguished: every evening, it is rekindled by veterans' associations in a simple and solemn gesture.

.jpg?t=17dd34a1_7cef_4edb_a5bf_05202457291f)

The Meaning of the Ritual: Remembrance and Unity

Every year on November 11th, the whole of France gathers.

In each town or village, in front of the war memorial, the ceremony follows an unchanging ritual:

• reading of the mayor's official message.

• A minute of silence at 11:00 a.m.

• Laying of wreaths.

• The Marseillaise.

• And finally, a moment of collective reflection.

There is no military parade: it is a moment of fraternity, shared between generations and backgrounds.

Mayors, veterans, legionnaires, students, and citizens stand side by side in front of the war memorial to honor courage and peace.

War Memorials

Between 1920 and 1925, more than 36,000 war memorials were erected in France.

Almost every village has one. Engraved on them are the names of those who “died for France.”

These monuments do not celebrate war: they bear witness to absence, collective mourning, and living remembrance.The November 11th ceremonies are still held there today, serving as a link between the past and the present.

For those who chose France

For former legionnaires, November 11th holds a special significance.

Many were not born on French soil, but chose France and its flag, sometimes at the cost of their lives.

The Foreign Legion and the Great War

More than 40,000 legionnaires fought under the French flag between 1914 and 1918.

Coming from more than 50 nations, they distinguished themselves on all fronts: Artois, Champagne, Verdun, the Somme…

Their courage left a lasting impression, and many now rest in France’s military cemeteries.

Their commitment symbolizes the Legion’s motto:

“Honor and Fidelity.”

In this, they share the fate of the World War I veterans: to serve their adopted homeland with courage and loyalty, whatever their origins.

Participating in the commemoration means entering the living memory of the nation, alongside those who fought before us and those who adopted us.

It means saying, in silence: “We remember. We continue with you.”

A legacy of peace and fraternity

November 11th is therefore not a celebration of victory, but a reminder of the price of courage, peace, and solidarity.

It is the day when France remembers those who, out of duty, stood up to horror.

It is also an invitation to protect peace and fraternity among peoples, values dear to the French Foreign Legion.

“Let us remember, so that we never relive this.”

Every citizen, every legionnaire, by participating in this ceremony, the oath of the soldiers: do not forget, remain faithful, serve France with honor.

It is the day when France remembers those who, out of duty, stood up to horror.

It is also an invitation to protect peace and fraternity among peoples, values dear to the French Foreign Legion.

“Let us remember, so that we never relive this.”

Every citizen, every legionnaire, by participating in this ceremony, the oath of the soldiers: do not forget, remain faithful, serve France with honor.

When French Youth Romanticizes Red Dictators

By Louis Perez y Cid

From Lenin to Mao, from Che Guevara to Hamas, a segment of French students continues to identify with revolutionary figures whose legacy is tragic.

This fascination speaks volumes about the political and moral disarray of a generation searching for an ideal. In lecture halls and on protest placards, the faces of Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, Mao, and Che Guevara are still proudly displayed. More recently, the Hamas flag has even appeared in student marches.

A glaring paradox: these young people, who demand freedom, justice, and the dignity of nations, turn to those who, throughout history, have silenced their own people.

.jpg?t=17dd34a1_7cef_4edb_a5bf_05202457291f)

The Revolution as a Romantic Myth

In the activist imagination, the “great revolutionaries” embody resistance to oppression, the emancipation of the masses, and the struggle against imperialism. Lenin and Stalin become the architects of a more just world, Mao the liberator of the Chinese people, and Che the romantic hero who fell with arms in hand.

But behind the posters and stylized T-shirts, historical reality fades: camps, famines, repression. Millions of deaths, erased with a stroke in the name of the “cause.”

Here, ideology triumphs over truth. It is not history that is venerated, but the myth, that of pure struggle, of the ideal against the brutality of reality.

But behind the posters and stylized T-shirts, historical reality fades: camps, famines, repression. Millions of deaths, erased with a stroke in the name of the “cause.”

Here, ideology triumphs over truth. It is not history that is venerated, but the myth, that of pure struggle, of the ideal against the brutality of reality.

The Selective Memory of a French Tradition

It must be said that French academic culture maintains a long-standing familiarity with the radical left. In classrooms and in some textbooks, communism is still presented as a noble idea, simply “perverted” by its excesses.

The crimes of Nazism are unanimously condemned; those of Stalinism or Maoism, however, are often downplayed. As if “generous” intentions excused mass graves.

This selective memory perpetuates a persistent moral bias: the revolutionary left is supposedly on the side of good, even when it has created numerous gulags.

The crimes of Nazism are unanimously condemned; those of Stalinism or Maoism, however, are often downplayed. As if “generous” intentions excused mass graves.

This selective memory perpetuates a persistent moral bias: the revolutionary left is supposedly on the side of good, even when it has created numerous gulags.

A Quest for an Ideal in a Disillusioned World

The enduring success of these red icons is also explained by the void they fill.

Today’s youth are growing up in a world saturated with crises—ecological, social, and political—where the horizon seems blocked. Traditional politics no longer inspires, and grand collective narratives have collapsed.

So, Lenin or Che Guevara reappear, not as political role models, but as symbols of the absolute. A way of saying no, of rebelling, of belonging to something greater than themselves.

Today’s youth are growing up in a world saturated with crises—ecological, social, and political—where the horizon seems blocked. Traditional politics no longer inspires, and grand collective narratives have collapsed.

So, Lenin or Che Guevara reappear, not as political role models, but as symbols of the absolute. A way of saying no, of rebelling, of belonging to something greater than themselves.

.jpg?t=17dd34a1_7cef_4edb_a5bf_05202457291f)

From Che to Hamas: the confusion of symbols

This same reflex is found today in the pro-Hamas slogans that are flourishing in some universities.

Many young people are demonstrating out of compassion for the Palestinian people, a just cause, of course. But in the marches, we also see those who wave the green flag without understanding what it represents: an authoritarian, homophobic Islamist movement that oppresses its own people as much as it fights Israel.

The pattern is the same as yesterday: the “resistance fighter” is sanctified, even when they become a perpetrator. Ideology simplifies everything: it is enough to be “against” something to be on the right side of history.

Many young people are demonstrating out of compassion for the Palestinian people, a just cause, of course. But in the marches, we also see those who wave the green flag without understanding what it represents: an authoritarian, homophobic Islamist movement that oppresses its own people as much as it fights Israel.

The pattern is the same as yesterday: the “resistance fighter” is sanctified, even when they become a perpetrator. Ideology simplifies everything: it is enough to be “against” something to be on the right side of history.

Between naivety and collective responsibility

Should we therefore condemn these young people? No. Their indignation is sincere, their thirst for justice real. But their judgment falters.

The problem isn't commitment, it's blindness. And this blindness is rooted in an intellectual environment where people have long preferred to turn a blind eye to "friendly" crimes.

The university, a place of knowledge and debate, should be a place where one learns to think critically, to confront myths with reality, and not to confuse freedom with revolution.

It's not the thirst for ideals that should be blamed, but the political romanticism that distorts it.

Because by constantly fantasizing about dictators as heroes, we end up forgetting what freedom owes them: the truth.

The problem isn't commitment, it's blindness. And this blindness is rooted in an intellectual environment where people have long preferred to turn a blind eye to "friendly" crimes.

The university, a place of knowledge and debate, should be a place where one learns to think critically, to confront myths with reality, and not to confuse freedom with revolution.

It's not the thirst for ideals that should be blamed, but the political romanticism that distorts it.

Because by constantly fantasizing about dictators as heroes, we end up forgetting what freedom owes them: the truth.

Ceremony at the Montferrat Cemetery (Upper Var)

November 2, 2025

They came, they were all there, those from the Upper Var, those from Toulon, Cannes, Puyloubier-Aix, and many others, in honor of the twenty-two legionnaires who rest there.

Some time ago, one of our comrades titled one of his columns: “The Forgotten Legionnaires.”

He wrote:

“Death forgives nothing, forgets no one; sooner or later she seizes us under her dark cloak and accompanies us with her fetid breath to the depths of the Styx or propels us, haloed in glory, toward the ethereal heights…”

On November 2nd, at the Montferrat Cemetery, we were there precisely so that they would not be forgotten.

We were there to rekindle the memory of the courage and sacrifice of the twenty-two legionnaires who rest in this place—men of duty who gave so much to France during the construction of the Canjuers camp.

Albert Camus, in A Happy Death, wrote:

“When I look at my life and its secret color, I feel a trembling of tears. Like this sky, it is at once rain and sun, noon and midnight.” It was raining on November 2nd in the Montferrat cemetery: rain on our heads, rain in our hearts. We walked together, a stretch of this path of remembrance and loyalty. For the first time here, the ceremony was enhanced by an honor guard from the Mother House.

We were there to rekindle the memory of the courage and sacrifice of the twenty-two legionnaires who rest in this place—men of duty who gave so much to France during the construction of the Canjuers camp.

Albert Camus, in A Happy Death, wrote:

“When I look at my life and its secret color, I feel a trembling of tears. Like this sky, it is at once rain and sun, noon and midnight.” It was raining on November 2nd in the Montferrat cemetery: rain on our heads, rain in our hearts. We walked together, a stretch of this path of remembrance and loyalty. For the first time here, the ceremony was enhanced by an honor guard from the Mother House.

Montferrat is the commune in the Haut-Var region to which Canjuers, the largest military camp in Western Europe (35,000 hectares, 35 kilometers long), belongs, both civilly and administratively.

The Legion operated there from 1968 to 1984, under three successive designations—CPLE/1st RE, CTL/61st BMGL, and C.R.T.R.L.E/1st RE—to build this exceptional training camp for the French Army, initially reinforced by a company from the 5th Foreign Engineer Regiment.

This day of remembrance owes much to the personal involvement of Major (ret.) Pierre Jorand, who spared neither time nor effort to ensure that this tribute was at once rigorous, dignified, and fraternal.

Time flies, hours and days fade, but it is up to us to remember what must be remembered: where the Foreign Legion left its mark, where brothers in arms rest.

Isn't it said that the Legion never abandons its own, and that—on the land steeped in the blood of legionnaires—the sun never sets?

We will not forget you.

The Legion operated there from 1968 to 1984, under three successive designations—CPLE/1st RE, CTL/61st BMGL, and C.R.T.R.L.E/1st RE—to build this exceptional training camp for the French Army, initially reinforced by a company from the 5th Foreign Engineer Regiment.

This day of remembrance owes much to the personal involvement of Major (ret.) Pierre Jorand, who spared neither time nor effort to ensure that this tribute was at once rigorous, dignified, and fraternal.

Time flies, hours and days fade, but it is up to us to remember what must be remembered: where the Foreign Legion left its mark, where brothers in arms rest.

Isn't it said that the Legion never abandons its own, and that—on the land steeped in the blood of legionnaires—the sun never sets?

We will not forget you.

The municipality offered a reception to the participants, and this wonderful gathering continued with a superb lunch, punctuated by Legion songs.

The atmosphere was warm, almost timeless. At times, everyone relived those great moments of brotherhood that never truly fade.

Ret. Commander Christian Morisot

The atmosphere was warm, almost timeless. At times, everyone relived those great moments of brotherhood that never truly fade.

Ret. Commander Christian Morisot

The strongest's reason is always the best,

And the art of cloaking injustice in law, the surest way to endure.

In a land said to be prosperous,

Lived a Wolf dressed in flags, numbers, and fine words.

Under the guise of order and progress,

He sniffed even into the pockets of sleeping sheep.

One morning, a Lamb named Citizen

Drank from the source of his labor.

He counted his coins, modest and honest.

The Wolf appeared, bearing a brand-new decree:

"Who gave you permission to drink without a bill?"

"Sire, this is my water, my labor, my rent."

"Nothing is yours," said the Wolf, sneering,

"For everything belongs to you through me." And with a legal gesture, he established his tax:

on water, air, wool, light, and even sleep.

Then, gravely, he declared:

“The free citizen contributes to the greatness of the State.”

The Lamb, shorn to his shadow, replied:

“So now I am free of everything, except you.”

But the Wolf, deaf, added another levy:

silence.

MORAL:

When power devours under the pretext of serving,

The people have nothing left but to bleat to drown out the noise of the shearing machine... or

The Eagle, perched on an old missile,

held a blue and gold trident in its beak.

The Bear, lured by the smell of gunpowder,

came out of its den, looking outraged:

"Hey! Hello, great bird of the skies,

Always quick to hover over the fires!

How noble your plumage is, how loud your cry resounds,

One would think that peace is born on your shores!

But tell me, this glittering trident,

What are you doing so close to my field?

This jewel, I believe, was carved in my forge,

And its hilt, long ago, marked my sea."

The Eagle, flattered by such a false tone,

wanted to be king, defender, hero.

He shouted loudly, beat his wings...

And the trident fell, a cruel thing. The Bear leaped, took it, and clasped it in his paw,

Roaring: "I take back what was in my haste!"

The Eagle, vexed, called his friends:

The owl*, old Europe, and a few hummingbirds

They all came to chirp: "Let go of this trophy!" Worried, however, they stayed away.

But the Bear, growling, remained camped.

Moral:

"Between the Eagle who promises and the Bear who takes, the Trident bleeds and the owl watches, counting the penalties as others count sheep."

*The owl. Wise, observant, but often motionless and silent, she sees everything... and does not move.

held a blue and gold trident in its beak.

The Bear, lured by the smell of gunpowder,

came out of its den, looking outraged:

"Hey! Hello, great bird of the skies,

Always quick to hover over the fires!

How noble your plumage is, how loud your cry resounds,

One would think that peace is born on your shores!

But tell me, this glittering trident,

What are you doing so close to my field?

This jewel, I believe, was carved in my forge,

And its hilt, long ago, marked my sea."

The Eagle, flattered by such a false tone,

wanted to be king, defender, hero.

He shouted loudly, beat his wings...

And the trident fell, a cruel thing. The Bear leaped, took it, and clasped it in his paw,

Roaring: "I take back what was in my haste!"

The Eagle, vexed, called his friends:

The owl*, old Europe, and a few hummingbirds

They all came to chirp: "Let go of this trophy!" Worried, however, they stayed away.

But the Bear, growling, remained camped.

Moral:

"Between the Eagle who promises and the Bear who takes, the Trident bleeds and the owl watches, counting the penalties as others count sheep."

*The owl. Wise, observant, but often motionless and silent, she sees everything... and does not move.

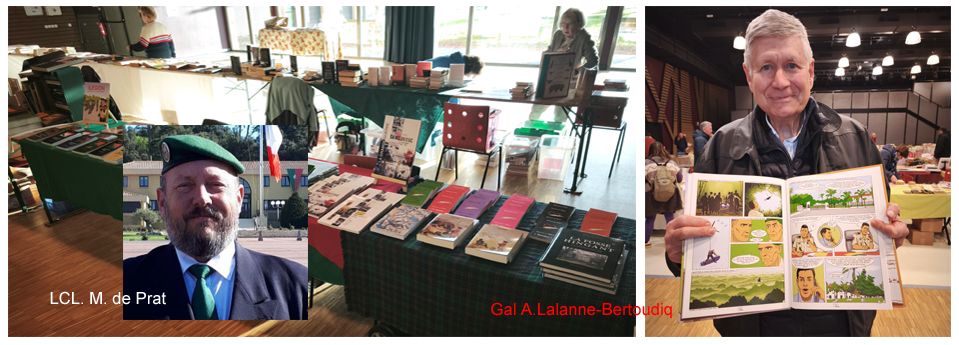

Saint-Coulomb: When a general discovers he's in a comic book!

At the book fair, the Legion makes its way between the pages and the speech bubbles.

By Louis Perez y Cid

At the Saint-Coulomb (Ille-et-Vilaine) book fair, retired Lieutenant Colonel Mickaël De Prat presented his books to the public. An active member of the Légion'Arts association, he also exhibited the comic book "C'est la Légion" (It's the Legion), published by the association and dedicated to authentic anecdotes from the French Foreign Legion.

Among the visitors, retired General Alexandre Lalanne-Bertoudicq, a resident of a neighboring village, stopped by the stand to greet his former comrade from the Legion, whom he had met at the 3rd Foreign Infantry Regiment (3e REI) in French Guiana. Surprise and smiles awaited: while leafing through the album, the general discovered that he himself appeared in one of the stories, illustrating a memory from his time commanding the regiment.

The Légion’Arts association warmly thanks the general for authorizing the publication of this anecdote, with the assistance of Commander Christian Morisot.

And for a touch of humor: the general has blue eyes… but in the comic, they are brown. The authors readily laugh about it, “we admit our mistake,” they promise, with a smile.

At the Saint-Coulomb (Ille-et-Vilaine) book fair, retired Lieutenant Colonel Mickaël De Prat presented his books to the public. An active member of the Légion'Arts association, he also exhibited the comic book "C'est la Légion" (It's the Legion), published by the association and dedicated to authentic anecdotes from the French Foreign Legion.

Among the visitors, retired General Alexandre Lalanne-Bertoudicq, a resident of a neighboring village, stopped by the stand to greet his former comrade from the Legion, whom he had met at the 3rd Foreign Infantry Regiment (3e REI) in French Guiana. Surprise and smiles awaited: while leafing through the album, the general discovered that he himself appeared in one of the stories, illustrating a memory from his time commanding the regiment.

The Légion’Arts association warmly thanks the general for authorizing the publication of this anecdote, with the assistance of Commander Christian Morisot.

And for a touch of humor: the general has blue eyes… but in the comic, they are brown. The authors readily laugh about it, “we admit our mistake,” they promise, with a smile.

Message of Support for Our Comrade Jean-Claude POU

Dear Comrades,

Our friend Jean-Claude is once again facing an ordeal that would crush many men. Today, he will have to undergo another amputation, that of his second leg.

We who knew Jean-Claude in the army know what he is made of. From a simple legionnaire, his courage and valor led him to the rank of captain. After giving so much to the Legion, he chose to build a peaceful life, a warm home to raise his two children, far from the hustle and bustle of the world.

Fate was harsh. The sudden loss of his beloved wife was a terrible blow, a pain from which no one emerges unscathed. A father above all, Jean-Claude drew on his strength, despite the grief, for his children, showing a resilience that commands respect.

Then came the first confrontation with illness, which took one of his legs. Despite this severe handicap, he continued to fight with remarkable dignity, preserving his independence thanks to his own courage and the invaluable support of his daughter, Marie.

Today, the fight begins again. Faced with this new and difficult ordeal, our comrade needs us more than ever. We must offer him the moral and fraternal support he so richly deserves.

Let us not leave him alone in this difficult hour. A message, a call, a thought can be a light in this ordeal. Let us remind him that once a comrade, always a comrade, and that Legionary brotherhood is not an empty phrase.

Jean-Claude is hospitalized at the:

Saint-Joseph Clinic

In Marseille

Room 22-32

Telephone: 06.08.86.45.70

Let us surround him with our unwavering brotherhood. For the Legion!

For Jean-Claude!

Commander Christian Morisot