Second Letter on Algeria

During the French occupation of Algeria, much ink was spilled. Louis, Antoine, and I ourselves have produced narratives that, in my opinion, only reflect a portion of what our memories retain, and freedom of expression has its limits, at the very least the limit of not always being right. Many journalists and intellectuals, both Left and Right, submit to the established order today, not daring to challenge those times when the subservient pen recounts the official narrative.

Next to several years after Algeria's independence, however, we continue to delve into the dark decades that marred this Franco-Algerian war.

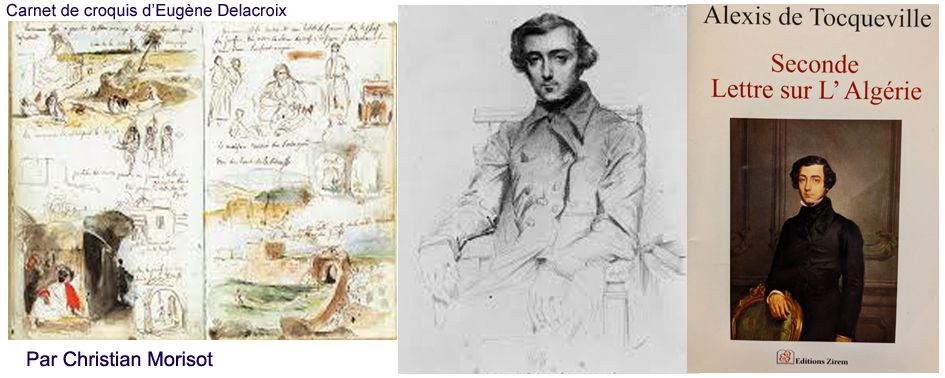

In 1831, the year the Legion was created, Alexis de Tocqueville was fascinated by the conquest of such an interesting Mediterranean country, he said! He explains this interest: “It is not enough to have conquered a nation to be able to govern it; the ideal was to conduct the conquest with a thorough understanding of that society, after having analyzed it carefully.”

Thus, Tocqueville embarks on his study and publishes two letters. The one that interests us is the second, concerning Algeria. He attempts to understand the historical and geographical conditions, the languages, the laws, the customs, the values, and the religion of the country. One observation is inescapable: the superiority of the “French race” is omnipresent in the letters addressed to the highest levels of the French state. Thus, we can read: “We are more enlightened and stronger than the Arabs; this people can only be studied with weapons in hand.” It is also inescapable that, at no point does Tocqueville question the legitimacy of the conquest of Algeria, but rather takes the opportunity to resolutely advocate for the abolition of slavery. In fact, between 1837 and 1847, Tocqueville sought to halt France's decline and restore its prestige and power, while remaining convinced that without a vigorous policy, the country would soon be relegated to second place and the monarchy threatened in its very existence. In this context, withdrawing from Algeria would be irresponsible. For Tocqueville, it was essential to remain, and the government should encourage the French to settle there in order to dominate the country and control the central Mediterranean through the construction of two major military and commercial ports: Algiers and Mers El-Kébir. The publication of Tocqueville's writings on Algeria is unprecedented, and his works, though little known to the general public, are nonetheless of considerable importance, even if they were written for the colonial authorities.

Second Letter on Algeria (1837) Alexis de Tocqueville.

“I suppose, sir, for a moment that the Emperor of China, landing in France at the head of a powerful army, seizes control of our major cities and our capital. And that, after destroying all public records before even bothering to read them, and abolishing or dispersing all the administrative bodies without being informed of their various responsibilities, he finally seizes all the officials, from the head of government down to the rural constables, the peers, the deputies, and in general, the entire ruling class; and that he deports them all at once to some distant land. Do you not think that this great Prince, despite his military might, his fortresses, and his treasures, will soon find himself in a very difficult position to administer the conquered country?” that new subjects, deprived of all those who conducted or could conduct affairs, will be incapable of governing themselves without knowing the religion, the language, the laws, the customs, or the administrative practices of the country, and that he took care to remove all those who could have instructed him in these matters, will be unable to lead them. We did in Algeria precisely what I supposed the Emperor of China would do in France. For the conquest, war was waged against the Turks of Algiers, but after the battles and the victory, we soon saw that it is not enough to have defeated a nation to be able to govern it. Indeed, the civil and military government of the regency had been in the hands of the Turks. No sooner were we masters of Algiers than we hastened to gather all the Turks, without omitting a single one, and we transported this mass to the coast of Asia. In order to better erase the vestiges of enemy domination, we had previously taken care to shred or burn all written documents, administrative registers, authentic records, or anything else that might have perpetuated the trace of what had been done before us. I truly believe that the Chinese I mentioned earlier could not have done better.

Having destroyed the administration at its very core, the French leaders conceived the idea of replacing it with a French administration in the districts by militarily occupying them.

Imagine these indomitable children of the desert, entangled in the myriad formalities of our bureaucracy and forced to submit to the slowness, the rigidity, the paperwork, and the minutiae of our centralized system. With the Turkish government destroyed and nothing to replace it, the country was still unable to govern itself and fell into a terrifying anarchy. All the tribes hurled themselves at one another in utter confusion, and banditry became organized everywhere… It is undoubtedly very difficult to know where to draw the line when it comes to occupying a barbaric country. War ends nothing; it only prepares a more distant and more difficult theater for a new war. We must remind the Chamber that Algeria presents the strange phenomenon of a country divided into two entirely different regions, yet absolutely united by an indissoluble and close bond. From this, the conditions for war in Africa arose. It was no longer a question, as in Europe, of assembling large armies intended for mass operations, but of covering the country with small, light units capable of reaching the population on foot.

There is no government so wise, so benevolent, and so just that it could suddenly bring together and intimately unite populations so profoundly divided by their history, religion, laws, and customs. It would be dangerous and almost childish to flatter oneself on this.

Conclusion.

In our eyes, the former inhabitants of Algeria are merely an obstacle to be removed or trampled underfoot; If we were to enfold their populations, not to raise them in our arms toward well-being and enlightenment, but to extinguish and stifle them, the question of life or death would arise between the two races. Algeria would sooner or later become a closed field, a walled arena where the two peoples would have to fight mercilessly and where one of them would have to die…

.jpg?t=81d7e9e7_c4b3_4d2a_afb9_41740be3400a)

.jpg?t=81d7e9e7_c4b3_4d2a_afb9_41740be3400a)